St. Luke's Newsroom

When people thrive, communities grow stronger. Explore stories highlighting how St. Luke’s supports our patients, neighbors and communities, collaborates with nonprofit organizations to improve health, and celebrates team members, partnerships and milestones.

Featured Articles

Community Health & Engagement

Improving health together: St. Luke’s awards Community Health Improvement Fund grants to 113 organizationsOne of St. Luke’s goals is to create healthier communities by building strong partnerships, deliver measurable outcomes and maximizing our impact.

Read more News & Announcements from St. Luke's

View allAdvancing Community Health

Community Health & Engagement How St. Luke’s and a community partnership helped create ‘home away from home’ for recovering patient

St. Luke's partners with the community to create a safe place for healing.

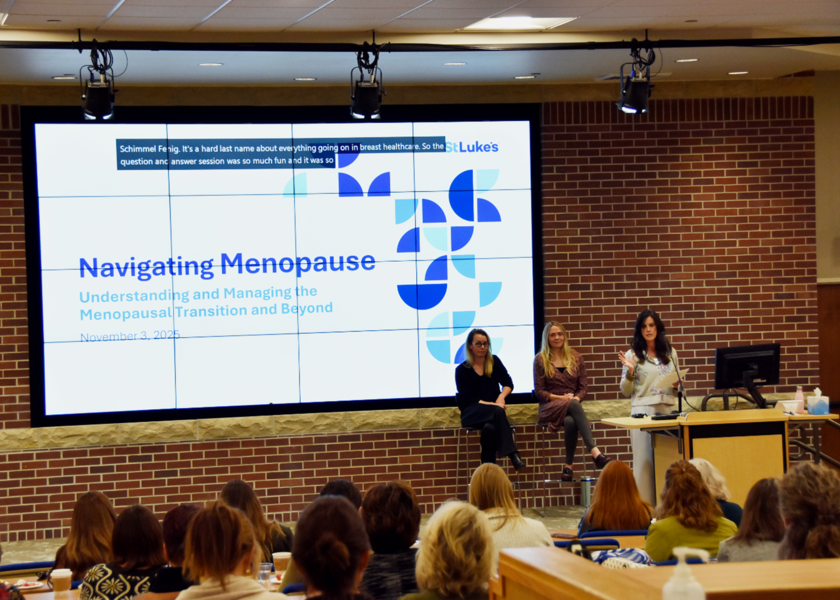

Community Health & Engagement St. Luke’s Women’s Forum empowers important health conversations in the Treasure Valley

What started as a simple idea has evolved into a gathering where hundreds of women have found comfort in sharing their stories and concerns.

Community Health & Engagement Improving health together: St. Luke’s awards Community Health Improvement Fund grants to 113 organizations

One of St. Luke’s goals is to create healthier communities by building strong partnerships, deliver measurable outcomes and maximizing our impact.

Community Health & Engagement Play Harder, Longer: St. Luke’s McCall Foundation’s campaign expands rehabilitation services and orthopedic care

St. Luke’s McCall Foundation recently launched its Play Harder, Longer campaign to raise $1.5 million in support of expanded outpatient rehabilitation therapy services and advanced orthopedic care.

PATIENT STORIES

Though her journey is far from over, Sofia's strength and determination are unwavering, and there's no doubt she will continue to make remarkable progress as she continues her rehabilitation.

St. Luke's 2025 Children's Miracle Network Champion, Sofia Rambow