Patient Care

Novel approaches at St. Luke’s lead to major reductions of in-hospital injuries

Teams in Boise celebrated their goal of zero preventable harm, making leaps in stopping common injuries that happen in hospitals. It was a multi-group effort that has provided great successes and cause for celebration, like with cookies!

By Dave SouthornLast Updated March 13, 2025

At St. Luke’s, safety is paramount. In virtually every corner, you will find that commitment, along with the goal of “zero preventable harm.”

That goes for frontline staff and patients alike.

Unfortunately, on rare occasions in medical settings, there are health care-acquired conditions that may lead to longer stays or may require further treatment. Such events occur at any medical facility, but St. Luke’s has made excellent strides as the result of a two-year effort to reduce the primary causes of those conditions.

“It aligned with that goal of zero preventable harm … we knew better performance was achievable,” said Bethany Rogers, system director of performance improvement. “We wanted to make sure it wasn’t sleepy background work, but to have it front and center.”

Though implementing major initiatives can take some time, the process was a success thanks to the frontline teams performing the actions and staff analyzing data to address weak points.

“Nurses and everyone on those floors have so many priorities, so our goal was ‘how do we make the right thing the easy thing?’” said Mandy Studebaker, a physician assistant and performance improvement specialist.

The three most common adverse conditions acquired at health care facilities — injuries from falling, hospital-acquired pressure injuries and catheter-associated urinary tract infections — were the focus of the “all hands on deck” push. And the results were outstanding.

Injury falls prevention

The most common injury in a clinical setting, St. Luke’s saw a 59% decrease in falls with serious injury from 2023 to 2024. The pilot location for the program, St. Luke’s Meridian, experienced a 21.3% decrease in total falls.

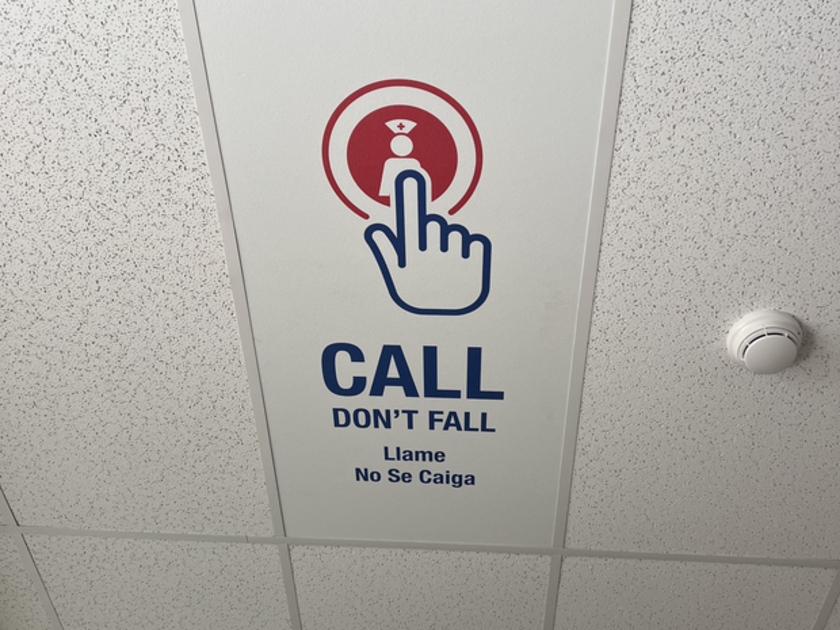

One portion of the falls prevention project included placing these signs on the ceiling of patient rooms.

Recently, the team on the sixth floor in the Meridian Medical Center was recognized for their significant progress in reducing patient falls. The unit is among the most challenging for fall prevention, seeing a high number of patients with behavioral health issues and cognitive impairments.

“Honestly, I was a little bit stunned at how well we did with our goals, reducing those serious injuries from patients falling,” said Stuart Carson, a performance improvement specialist. “The chart kept dropping, and it was like, ‘wow,’ especially in areas like that (in Meridian). It’s been really great seeing it around the system.”

So, how did the team do it?

In addressing fall risk, research showed that patients may not be fully aware of, well, how at-risk they might be. They are in a new environment, no carpet on the floor, a different bed, often taking medications and potentially connected to medical equipment … the list goes on.

Patient-facing whiteboards were created to help patients understand their unique fall risk factors, along with signage, such as “call, don’t fall,” to reiterate if they need to contact staff to get up.

And for frontline teams, it is small improvements, like streamlining documentation at the beginning of the patients’ stay, checking boxes in a report instead of having to write things out or communicating earlier about fall risks.

Formerly, a notation would be made on a patient’s door that they were high risk for a fall, but it was found that many falls came from those who thought they were at little to no risk.

“It informs fall status in a very clear way that is now standard for med-surg units across the system,” Carson said. “One of the biggest changes we made as a system was that everyone is a fall risk, which keeps it in mind for our teams but also the patients, too.”

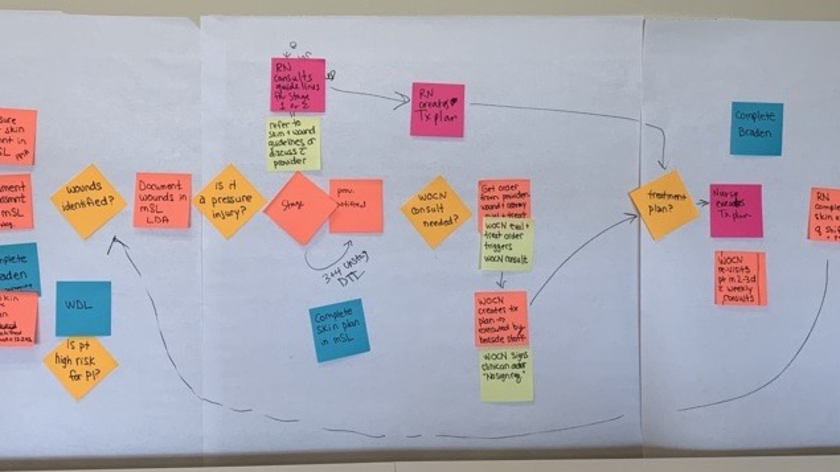

Hospital-acquired pressure injury prevention

A hospital-acquired pressure injury, known as a HAPI, is a localized injury that appears on the skin and extends to the tissue beneath, often near a bony part of the body, that can develop when there is prolonged pressure in one location.